Actively Care About Energy Savings? Try a Passive House

photo credit: wikipedia

The New York Times this weekend had an interesting article on passive houses, a building standard popular in Europe that reduces energy consumption for heating and cooling by 90% compared to a conventional home.

It has been a good deal more expensive to build, however, than the average home. That might partly explain why the passive-building standard is only now getting off the ground in the United States — despite years of data suggesting that America’s drafty building methods account for as much as 40 percent of its primary energy use, 70 percent of its electricity consumption and nearly 40 percent of its carbon-dioxide emissions.

Proponents of the standard, who note that passive homes often use up to 90 percent less heating and cooling energy than similar homes built to local code, say the Landaus embody the willingness of more homeowners to embrace passive building in the United States. Even Habitat for Humanity, the affordable-housing philanthropy, is now experimenting with the standard.

Yet the market remains minuscule, and the materials and expertise needed to build passive homes are often hard to find. While some 25,000 certified passive structures — from schools and commercial buildings to homes and apartment houses — have already been built in Europe, there are just 13 in the United States, with a few dozen more in the pipeline.

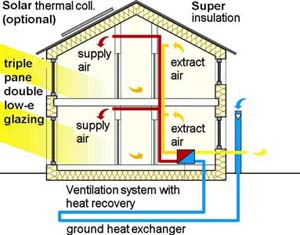

To achieve the passive house standard, homes are airtight and fitted with thick insulated walls and floors, triple-paned windows placed with extra care towards how much and what type of sun they receive, and a sophisticated ventilation system to maintain temperatures, all of which is calculated by a computer model.

The whole idea can start to seem a bit fussy though when the orientation for a pleasant view out the window cannot be had because it is not ideal for solar energy, or a fireplace is considered too inefficient, or the triple-paned windows had to be exported into the United States because an energy-efficient equivalent couldn't be found locally.

Like any other new technology that promises an energy-efficient future -- solar panels and electric cars -- the cost of early adoption can be prohibitively expensive now but payoff with time. The Times article estimated that it cost the builders an extra $50,000 to meet passive house standards, which would be earned back in energy savings within 10 years.

But with the median age of homes in the U.S. at 36 years, the basic concepts of a passive house can still be trickled down to currently inefficient homes by renovations such as reducing draft, better insulation, double-paned windows, or planting a tree outside to block summer sunlight.